It’s time to celebrate the town’s amazing – and complex – relationship with herring.

In 1889, William Root Bliss author of “The Colonial Times on Buzzard’s Bay,” wrote about the annual herring runs of the Plymouth Colony:

In early spring alewives came into the rivers, and for a while formed the staple of trade and conversation. Their annual return ‘with such longing desire after the freshwater ponds’ – as an old chronicler writes – was the most important event of the year. At the birth of the town the prosperity of alewives was a public concern; and from that day to this, these historic fishes have aroused the state legislature, have vexed town meetings, and have formed a platform on which the rising politician has aired his wisdom.

Today, we remember the historical and contemporary importance of the herring run with Plymouth’s 11th annual Herring Run Festival. It’s scheduled to begin on Friday, April 19, with a pregame party of sorts. Happy Hour with Happy Fish at the Plymouth Center for the Arts, from 5 to 8 p.m.

The event will feature talks by Alex Haro, emeritus biologist with the S.O. Conte Anadromous Fish Research Center in Turners Falls, and Jimmy Powell, director of the ecology program for the Jones River Watershed Association in Kingston.

You can expect to see many of Plymouth’s more thoughtful vernal celebrants in attendance, from resource managers to natural scientists to craft beer devotees. (Of note, the Indie Ferm brewery will be introducing its “Anadromous Ale” at the event. Anadromous is the formal term for fish that migrate from the ocean to spawn or feed in freshwater streams.)

On the next day, Saturday, April 20, the Plymouth Herring Run Festival itself a celebration of Earth Day (which is April 22) will take place at Jenney Pond Park, highlighting the extensive efforts taken to restore Town Brook’s fish habitat. It’s organized by the nonprofit bird conservation and science education group Manomet Inc. and promises live music, food trucks, games, art, and herring counts, among other activities. You can even learn about the town’s incipient efforts to develop a climate action plan.

According to Plymouth’s real-time video monitoring of the herring run at the Jenney Grist Mill on Town Brook, the herring have begun to arrive already. You can watch them live from the comfort of your couch, even sending in virtual counts, or you can sign up to help count them in person.

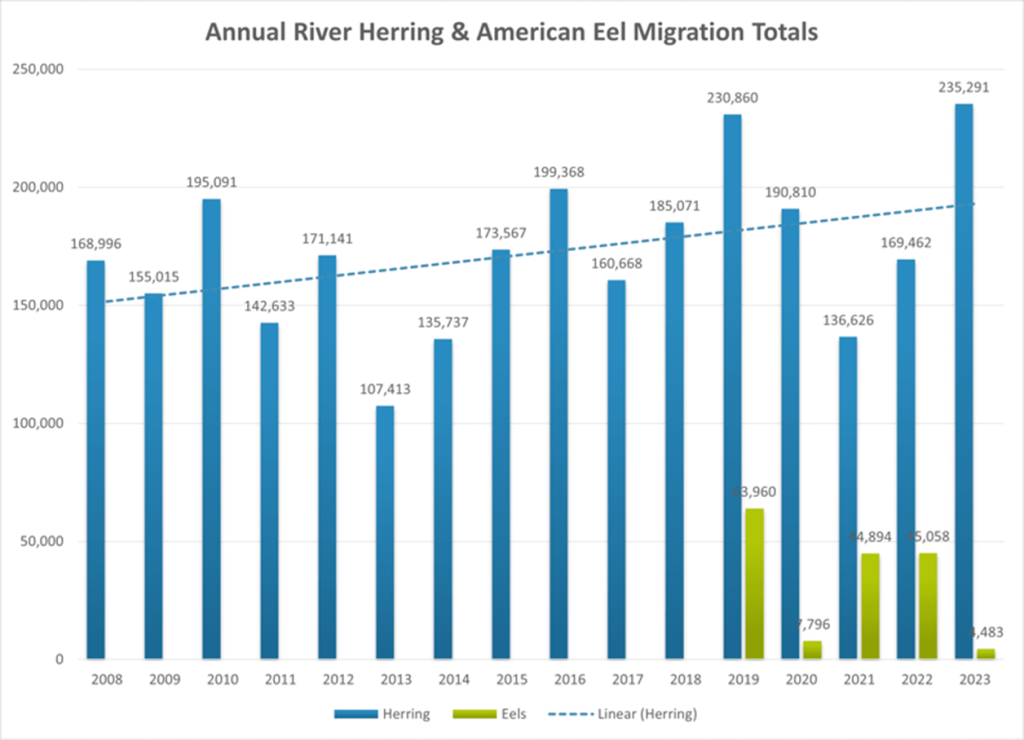

The first two intrepid fish arrived on March 29, more than a week before any others. More than 235,000 fish were estimated to run up Town Brook to Billington Sea in Morton Park last year. It has been estimated that Town Brook once may have accommodated between one and two million migrating fish each year. The chart below shows count data from 2008 through last year. It looks like an upward trend, but the time series is short and variable, so it’s too early to say that things may have changed because of several town habitat restoration projects.

The state Division of Marine Fishery believes that more than 100 streams in 50 Massachusetts municipalities support river herring runs. Plymouth is centrally important to the state’s herring runs, drawing fish from Buzzards Bay to the south and Cape Cod Bay to the east. While Town Brook is often the main focus of attention, herring will also run up the Eel River at the southeastern end of Plymouth Harbor; the mouth of Beaver Dam Brook at White Horse Beach and into Bartlett Pond; through Wareham and up into ponds along the Agawam River; through Buzzards Bay, into Buttermilk Bay, and up into Red Brook to White Island Pond; and through the Cape Cod Canal into the Herring River and up into Great Herring Pond. Other smaller runs may exist as well.

In collaboration with biologists from the University of Massachusetts Amherst and the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries, Plymouth’s Department of Energy and Environment has developed a mathematical model that uses underwater video sightings to estimate the total numbers of river herring that have migrated up Town Brook at any time during the run.

There are two species of river herring that comprise Plymouth’s herring runs: alewife Alosa pseudoharengus and blueback Alosa aestivalis. The two species are almost impossible to differentiate by visual inspection. The alewife tend to run first, however, and they are known to prefer quiet ponds at the head of the run, such as Billington Sea, as spawning sites. The blueback follow later, often spawning at more dynamic instream locations. The runs also are shared with the American eel Anguilla rostrata, a “catadromous” species that migrates upstream to live but eventually migrates back to the ocean to breed; the rainbow smelt Osmerus mordax, which tends to breed in the lower reaches; and the resident white sucker Catostomus commersonii.

River herring are now considered by the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission to be depleted to “historic lows” along the entire US east coast. The primary reason for this is likely the degradation or loss of habitat. But a 2017 assessment by the Commission of the size of several east coast river herring stocks found that the numbers of river herring were either increasing or stable in five Massachusetts rivers (but Town Brook was not assessed).

Importantly, Plymouth has accomplished more along Town Brook than most municipalities on the East Coast in bringing back habitat for river herring. Beginning in 2002, under the leadership of Plymouth DEE director David Gould, the town and its 13 partner agencies and organizations removed five dams, replaced four bridges, excavated contaminated sediments, replumbed stream channels, and created new riverine wetlands. This work has been splendidly recorded in a story map and with drone overflights in what I believe is one of the finest public presentations on the town’s website.

Initial concerns over potential adverse effects on the property values of homes along Town Brook as a result of the restoration work were unfounded, based upon a recent peer-reviewed study undertaken by DEE’s Mike Cahill. To the contrary, Cahill and his co-author found that “dam removal would not negatively impact waterfront property values, while it may translate into an overall environmental price premium for the community at large.”

Plymouth also has been a leader in the application of radio tags (called passive integrated transponder, or PIT tags) to track the movements of river herring during migrations both up and downstream and over multiple years. Only a few fish can be tagged, but they yield useful information about repeat migrations. According to Abigail Archer, a fisheries specialist with Woods Hole Sea Grant, four fish that were tagged initially in 2019 were detected – with an antenna stationed at Brewster Gardens – migrating up Town Brook last spring for the fifth year in a row.

With the recent Town Meeting approval of $3 million in Community Preservation Act funds to improve the trails at Jenney Pond Park through Brewster Gardens – including replacing the pedestrian bridge over Jenney Pond – the town’s efforts to enhance access to the restored habitat received a significant boost.

While all of the dams – except the Jenney Pond Dam at the site of the gristmill – on Town Brook have been removed, several critical projects still remain. These include the dredging of 6,350 cubic yards of sediment from the sometimes murky Jenney Pond, the creation of a “nature-like” bypass channel for migrating fish to circumvent the Jenney Pond dam and gristmill, and the replacement and widening of culverts in Morton Park leading to Billington Sea.

Charles Francis Adams wrote in 1982 that “It is singular now in studying the course of earlier town-life on the Massachusetts seaboard, to notice the importance of the alewives.” This enduring connection to nature is reinforced through Plymouth’s celebration of the herring run. All the Town Brook restoration projects have been designed both to enhance fish habitat and to improve the public’s ability to experience nature in the middle of Plymouth’s Historic District. Including the works to date and those planned for the future, there is much to be excited about at the upcoming Herring Run Festival.

Plymouth resident Porter Hoagland is interested in local environmental and natural resource matters. He welcomes your feedback, and he can be reached at phoagland@whoi.edu.