In December 1773, Boston was a tinderbox ready to burn. The Tea Tax implemented earlier that year had the Sons of Liberty group and other concerned citizens up in arms over yet another attempt by British Parliament to usurp their rights as freeborn Englishman. In desperation, they turned to “mother Plymouth” for assistance.

Only too happy to oblige were descendants of the Pilgrims – self-proclaimed Separatists. Those dissidents sought religious freedom and established New England’s first permanent colony. A majority of townspeople backed the protests and agreed to “protect our worthy friends of Boston” when called upon.

A letter sent by Plymouth leaders may have helped fan the flames of discontent – and likely added fuel to the fire of freedom. The correspondence was published in newspapers 250 years ago on Dec. 16, 1773 – the same day enraged Bostonians stormed Griffin’s Wharf and dumped 342 chests of tea in the harbor.

Plymouth was one of several communities that stood with its fellow citizens in Boston. Residents of Lexington, Wakefield, Marshfield, and other towns also voiced their support for the defiant stance taken in Boston against the 1773 Tea Tax.

“This is very important,” says Donna Curtin, executive director of Pilgrim Hall Museum, which also includes an extensive archive of 18th-century artifacts and manuscripts. “These expressions show how local communities are sharing and assessing information taking place across the colonial world, and coming to unprecedented conclusions.”

Plymouth, however, stood alone by making a bold statement for liberty. Its message – or rather, what was missing from it – could be perceived as a direct challenge to the Crown.

“It’s really one of the first sets of resolves which does not begin with ‘We are loyal subjects to his majesty the King,’” says Jonathan Lane, Revolution 250 coordinator for the Massachusetts Historical Society and a former Plymouth resident who worked at Destination Plymouth for several years. “That gets omitted in this letter, and I think that is an important point.”

News of the Tea Act approved in 1773 by British Parliament was not received well in America. It followed the much-hated Stamp Acts of 1765 and Townshend Acts of 1767, which imposed duties on various products – including tea – imported by the colonies. Both acts were intended to help the English recoup the cost of the French and Indian War of 1754-1763 and for maintaining troops in America.

While the colonies probably didn’t like the idea of paying taxes, they were most upset by the fact that these levies were imposed without American representation in Parliament. This was viewed as an abridgement of their rights as English citizens.

New York, Philadelphia, and other major ports also protested the Tea Act by refusing to take delivery of everyone’s favorite hot beverage. Crates of tea sat unloaded in ship’s hulls or languished on wharves in mostly uneventful remonstrations.

Except in Boston. Tea was delivered to the bustling harbor on Nov. 28, 1773, but residents refused to allow the cargo to be unloaded. Thomas Hutchinson, the royal governor of the province of Massachusetts, took a hardline stance and insisted the tax would be collected – one way or another. The deadline to pay the revenues was Dec. 16.

Samuel Adams and other members of the Sons of Liberty, a radical and occasionally violent colonial political group, took umbrage to that demand. Meetings were organized in several towns to voice disapproval of the decision by Hutchinson, who claimed he was “his Majesty’s representative in this province,” according author and historian Stacy Schiff in “The Revolutionary Samuel Adams.”

In a rebuke of the aging governor, Adams said, “He? He? Is he that shadow of a man, scarce able to support his withered carcass or horary head – is he representation of majesty?”

A year before, Adams had written James Warren – a Plymouth resident who supported liberty for the colonies – about “tyrants and tyranny.” He exhorted New England’s first permanent settlement to stand up and be heard.

“I wish mother Plymouth would see her way clear by appointing a committee of communication and correspondence,” Adams said in his letter.

After fending off Tory opposition, Plymouth eventually responded to Adams’s plea and agreed to meet about the tea protest.

“That’s what Sam was good at,” Lane says. “His real gift was bringing people together in common cause. He sends out a pamphlet to all 250 towns in Massachusetts and asks them to form committees of correspondence and talk about how they feel about their rights being abridged. This spills over into the Tea Act.”

On Dec. 7, Plymouth convened a meeting to look at that issue. Warren, William Watson, and Deacon John Torrey were appointed to serve on the town’s Committee of Correspondence – essentially an extension of the liberty movement – which then called a Town Meeting.

Voters agreed to “protect our worthy friends of Boston… at the hazard of our own lives and fortunes will exert our whole force to defend them, against the violence and wickedness of our common enemies.” Town Clerk Ephraim Spooner certified the resolutions and sent them to the Committee of Correspondence in Boston, as well as the town’s newspapers.

“In the case of the Plymouth letter, it is drafted by a committee of town meeting, signed by the town clerk, so it’s a public and official response in support of ‘the rights and interests’ of America and against measures by the British ministry,” Curtin says.

In those days, Boston newspapers published once a week. By time the Plymouth letter arrived and appeared in print it was Dec. 16. Readers had enough time to digest that information before attending a gathering that evening at Old South Meeting House. As many as 7,000 people congregated outside the church where Adams spoke about the protest.

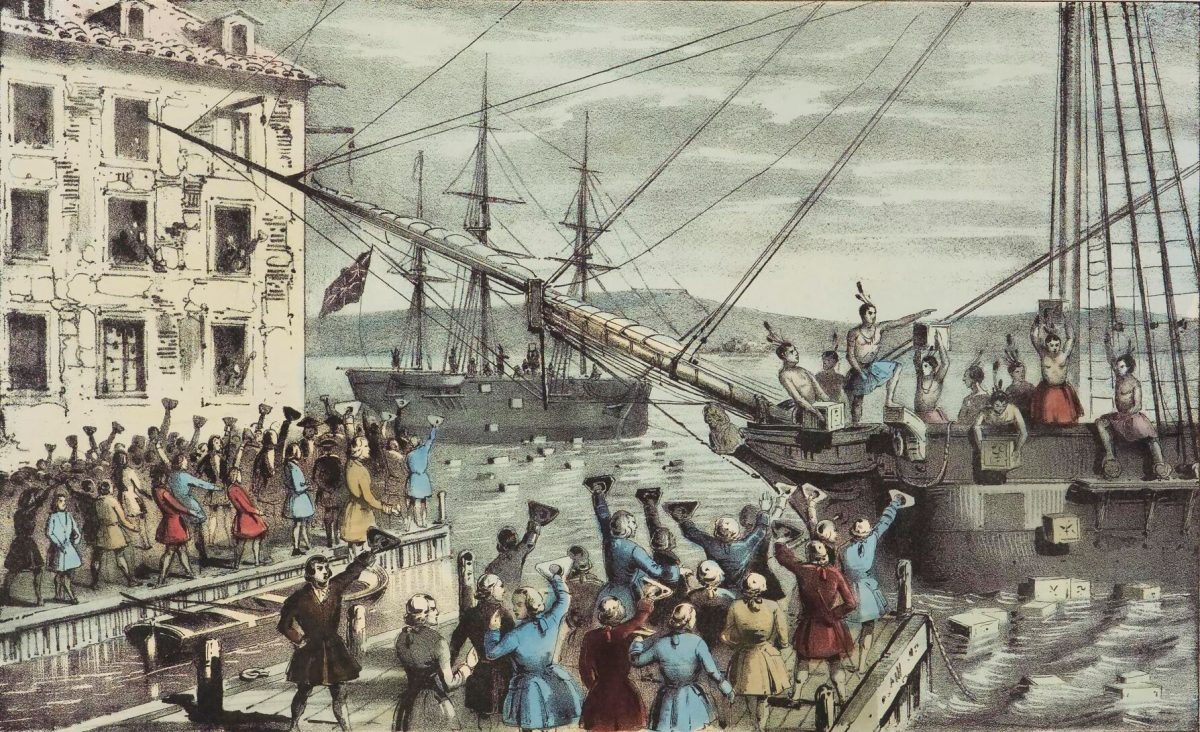

As the meeting dragged on, people began to leave. Adams urged them to stay but some appeared to have another plan in mind. A large number of patriots outside the meeting house followed this smaller group – some of whom wore Native American outfits while others had faces blackened with soot to disguise their appearances – to Griffin’s Wharf. The protestors stormed the ships and threw 92,000 pounds of tea into the harbor. The East India Co. reported the loss to be £9,659, or nearly $2 million today.

After the Plymouth vote, local Tories tried to rescind it. According to research by historian Mary Blauss Edwards, Edward Winslow Jr. – a Pilgrim descendant – attempted to have a letter in opposition to the earlier decision read at a town meeting on Dec. 13. His request was shot down by a vote of 52 to 20. By this time, Plymouth was firmly behind the cause of liberty.

“The town has been interested in and attendant to the rights of their country,” Lane says. “They recognize that measures being adopted by the British ministry go against the rights and liberties of the people. They are looking for every possible method to support that. The importing of tea by any person subject to a tax without our consent is an evil with which they cannot abide.”

Winslow had a good reason to support the Crown – he was one of those who stood to gain from the Tea Tax. The act in effect created a monopoly for the East India Co., which controlled commerce with Southeast Asia. Winslow, along with Hutchinson’s sons, were New England partners with the mammoth trading company.

“These are people who are benefitting directly from this profit, which is going to give a monopoly to certain individuals,” Lane says. “If you were a merchant, you used to able to write to your London factory and order tea to sell here. Now, you can only buy from certain individuals in America – and one of those individuals happens to be named Winslow. This is really what people are objecting to – the idea of a monopoly.”

It appears Winslow and his fellow Tories had not correctly gauged the political discontent of Plymouth at the time. His attempt to rescind the vote exposed a growing rift among townspeople, many of whom were lining up with the Sons of Liberty.

“In the 1770s, it (the Tea Act) affected the way disparate political opinions were perceived as events were unfolding in real time, and as people were actually making up their minds about what to think,” Curtin says. “Winslow and the leading Plymouth figures who signed on to his letter get caught in the uproar as the tea controversy becomes a crisis. It’s likely some of Winslow’s group hadn’t necessarily chosen a definitive side in the growing divide and saw their objections as measured, even if Winslow himself was vehement. The uncertainties of such moments are easy to overlook in examining the past.”

Winslow was one of the Tories who had to leave Plymouth because of his political beliefs. As the colonies inched closer to rebellion, the seeds of discontent grew. Winslow, viewed as “obnoxious,” was stripped of his offices in town government. He later writes how “the Great Mob. . . hunted me from the Country” in 1774. He eventually moved his family to live in a Tory community in Nova Scotia.

That same year, Plymouth decided to relocate its fabled rock from the waterfront to make room for wharf expansion. Several people wanted to move that symbol of Pilgrim pride and Separatist sentiment to Town Square, next to the Liberty Pole. When it was lifted, the rock split in two – another symbol of the growing divide in the town and country. The die had been cast.

“Plymouthians dragged Plymouth Rock up to the center of town,” Lane says. “That’s a pretty open move at that point.”

Dave Kindy, a self-described history geek, is a longtime Plymouth resident who writes for the Washington Post, Boston Globe, National Geographic, Smithsonian and other publications. He can be reached at davidkindy1832@gmail.com.