Given our town’s prominent role in the country’s early colonial life, perhaps it’s no surprise that the Gilded Age is a slice of history that hasn’t been explored in depth in Plymouth. But it is an era worthy of attention (even more so now with the interest generated by the HBO series), and I’ve devoted several lectures to the subject over the years.

Two luminaries from the time stand out. One was President Grover Cleveland, who spent a considerable amount of time in Plymouth and owned a building lot in Manomet as well as a hunting lodge in deep South Plymouth. The lot was never developed and the hunting lodge is now gone. (Cleveland’s main claim to fame was as the only president to serve two non-consecutive terms.)

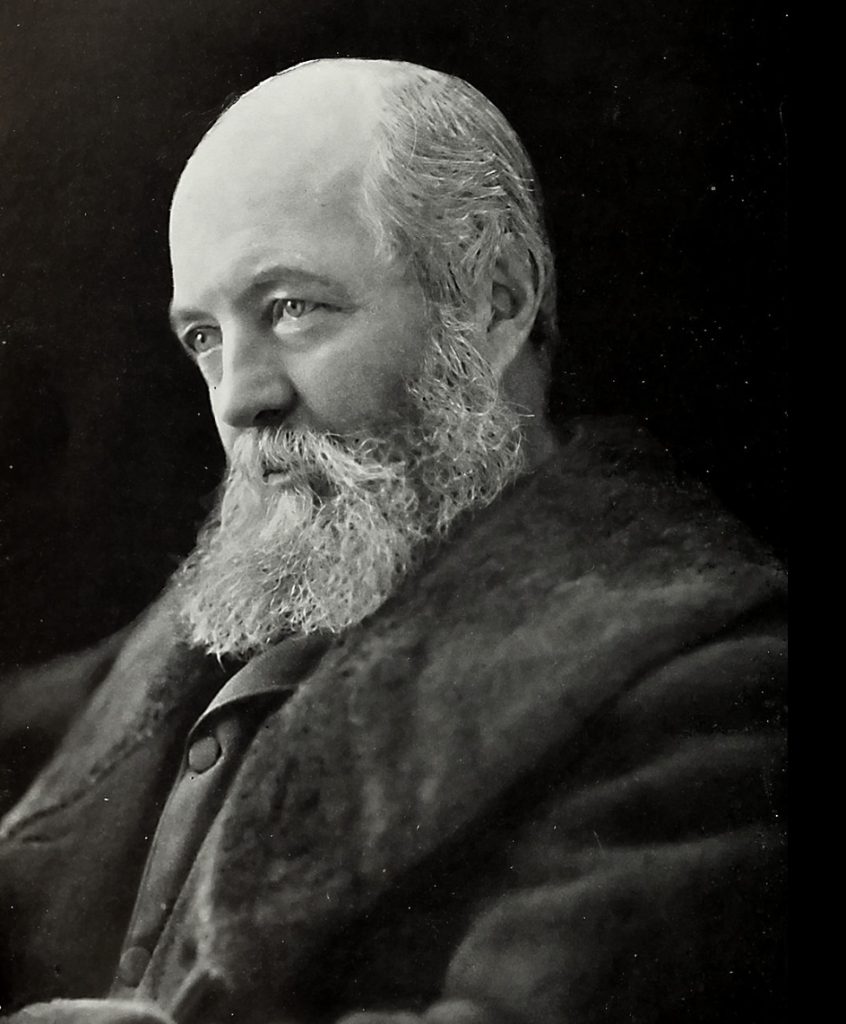

But Frederick Law Olmsted, America’s premier landscape architect at the turn of the 20th century, has had a far more lasting influence, both here in Plymouth and elsewhere in the United States. Olmsted (1822-1903) was born in Connecticut; extensively traveled the nation; tried his hand at journalism and gold mining; started a landscape business in New York in 1865; and finally established the country’s first recognized full time landscape architecture firm in Brookline in 1883. His home and studio are now a National Park site and worthy of a visit. Olmsted’s work includes New York City’s Central Park, the grounds of The U.S. Capitol, and Boston’s Emerald Necklace, among many other projects.

Olmstead’s original connection to Plymouth is still not entirely clear. I have been told by several people that Olmsted’s aunt owned the house at 219 Court St. and Olmsted spent some summers with her. I was also told that the land bounded by Court, Hall, Standish, and Olmsted was part of his family’s estate and Olmsted used the land as a nursery; several specimen plantings still remain.

Entirely true or not, the Olmsted archives show several layouts for these plots, including subdivisions and new road layouts. What is known for sure is that Olmsted’s daughter, Marion, lived at 212 Court St. in 1915 (#219 today) as well as 219 Court St. (possibly #210 today). By 1940 Marion’s home was owned by her brother Fredrick Law Olmsted Jr., who gave a piece of land to the town for the opening of Olmsted Terrace, connecting Court Street to Standish Avenue. Tracing deeds at the Registry is my next step, followed by a deep dive into the Olmsted family tree.

We also know that Olmsted provided Plymouth with design plans for three public parks.

The Training Green on Sandwich Street has been a public space in town since 1711. Used for militia training as well as a playground, the park’s first major improvement came with the erection of the Sailors and Soldiers monument in 1867. The Civil War memorial, inscribed with the names of 72 Plymouth men who fought and died in the War of 1861, was designed by Peter Blessington.

The monument was dedicated in 1869 and attended by a crowd of 5,000 people. Sometime in the late 1880s the Plymouth Park Commision hired Olmsted’s firm to redesign the park. In the Olmsted Archives are drawings dated 1889 and 1890. The final plan from 1890 was the one implemented.

In 1892 the Commissioners decided the Green should be “kept as an ornamental park, thereby increasing the beauty of the locality and the comfort of the neighborhood.” (Park Commissioners Report 1892)

The playground was relocated to the Nathaniel Morton Grammar school, enlarging what had already been a play area for children. I think it was a polite way of making the park a solemn place and war memorial, and it remains so to this day.

Olmsted designed two additional public parks in Plymouth, starting with Bates Park.

Bates Park is located at the corner of Allerton and Vernon streets. Originally known as Waverly Square, the plot of land was donated to the town by Moses Bates in 1856. The redesign by Olmsted was approved in 1892 and the park was rededicated to Bates. The cost of the park was $100, of which Olmsted was paid $11.91 for his services. The balance was for labor, settees, trees, shrubs, seeds, and three cornerstones. (Although it is difficult to compare the values of spending separated by more than a century, Olmstead’s fee, adjusted for inflation, amounts to about $400 today.)

Olmstead also planned Burton Park, which consists of two parcels, together totaling about an acre in size. The first was the parcel known as Jumping Hill, directly in front of the Mount Pleasant School. The second parcel, donated to the town by Nathaniel Morton, was a small strip of land located at the base of Jumping Hill. The plan called for filling the base of the hill and planting the hill with barberry, juniper, as well as clumps of pitch pine and white pines. The park’s plans also included a row of elms to be planted along Whiting Street. Olmsted’s fee for this park was the grandiose sum of $14.66 ($500 in 2023 dollars). In the late 1960s it was my dad’s favorite spot for watching the fireworks shot from Stephens Field.

It is not easy to find the plans among Olmsted’s published papers but a search of the online Olmsted archives site may lead you on an enjoyable journey down a rabbit hole to other amazing projects Olmsted created.

Upon Olmsted’s retirement in 1895, his sons Frederick Jr. and John took over the business and renamed the firm Olmsted Brothers. Their work was as notable as their fathers and included projects in Plymouth, including the Hornblower estate (now Plimoth Pawtuxet Museums), studies for the Knapp estate (the land bounded Court, Standish, Hall and Olmsted), and a few private residences.

I never tire of the fact that Olmsted worked, visited, and possibly lived in Plymouth. These articles often prompt memories and snippets of history from you that I may not be aware of. I always enjoy hearing from readers with their own stories to share.

Architect Bill Fornaciari, a lifelong resident of Plymouth, is the owner of BF Architects in Plymouth. His firm specializes in residential work and historic preservation. Have a question or idea for this column? Email Bill at billfornaciari@gmail.com.