As expected, the senior dance was a very formal affair. High school students were immaculately dressed for the occasion, marking the end of youthful innocence and the beginning of more mature pursuits. Girls were decked out in white gowns and wore gloves while boys sported white jackets with matching flannel pants.

Nearly eight decades ago, just about everything was different about high school. A strict dress code was enforced, and casual attire was not allowed at Plymouth High School. For classes, males were required to wear suits or sweaters with ties while females had to dress in skirts with the hemline below the knee – every day.

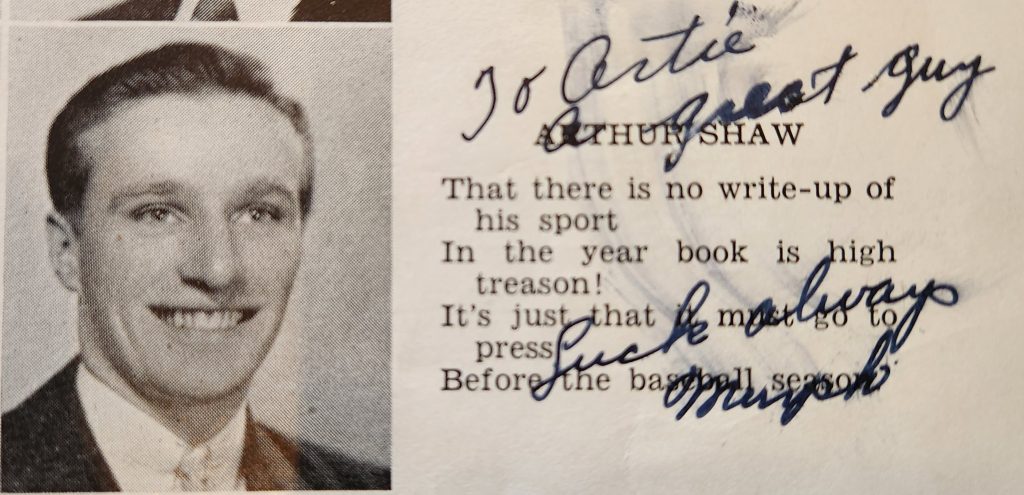

“There were no short-shorts,” recalled Artie Shaw, now 97. “There were no drugs, no cars, and you got a great education.”

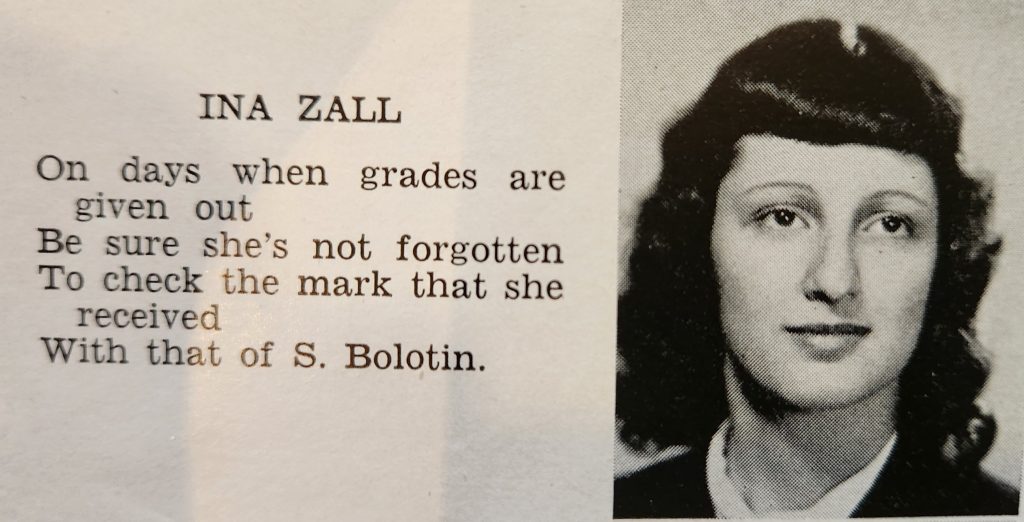

Shaw graduated with the Class of 1946, along with classmates Enzo Monti and Ina Cutler, whose last name was Zall back then. The three friends – along with a fourth, Betty (Besegai) Grozinger, who couldn’t make it this time – gather annually to commemorate their graduation.

“After the 70th anniversary, we said we would do this every year,” said Monti, who is 95. “Except for Covid, that’s what we’ve done.”

“We’re the remaining members of the Class of 1946 that we know about,” added Cutler, 95, who lives in Quincy. “There may be more of us out there, but we don’t know where they are.”

Some 78 years ago, 130 seniors graduated from Plymouth High School – compared with the more than 500 who received diplomas from Plymouth North and Plymouth South in 2024. Back then, there was only the one campus, located in what is now Nathaniel Morton Elementary School on Lincoln Street. Students from all over town – and beyond – attended classes there.

“I lived in South Carver in those days,” said Shaw, who remembers catching the school bus every morning at 6:45 a.m. He lives in Plymouth today and has ancient ties to the town. “I’m related to 18 Pilgrims,” he added.

All three recall their high school days with fondness, each proud of the education they received and the friendships they formed. Teachers were tough, discipline was the norm, and students didn’t question authority.

“It was a very different time, socially and culturally,” said Monti, 95, who still lives in North Plymouth, just a few blocks away from the house he was born in. “Young people did not have the choices they have today. We were very naïve.”

While educators could be strict, they were mostly fair and tried to ensure each student got the best education possible, the ’46 grads said. Several teachers stood out, including Alba Martinelli, who left Plymouth to join the U.S. Army during World War II and served on the staff of none other than General Douglas MacArthur.

“She was brilliant,” Monti recalled. “After she married, her name was Alba Thompson and she became the first woman selectman in Plymouth.”

Another tough but admired teacher was Alice Urann, who taught English. She tolerated little in the way of disturbances in her classroom and was known to make those who misbehaved write down their offense hundreds of times on paper. In his senior year, Shaw and others on the football team decided to take English together, figuring there would be safety in numbers. There wasn’t.

“She was wise to us and kept us all in line,” he said. “She called us her ‘cherubs.’”

Shaw said student-athletes played a tougher brand of football in those days, wearing little padding for protection. “We had leather helmets with earflaps and no facemasks,” he said.

Monti recalled a formative experience in high school that shaped his later life. There were few elective courses in those days, but he had the chance to take a semester of psychology. The class left a deep impression on him.

“It was fortunate because that led me to my career as a psychologist,” he said. “I worked in schools around the country before returning to Plymouth.”

Growing up during World War II was not easy. Many teachers, and even some students, left high school to join the war effort. Curfews were in effect across Plymouth and all lights had to out or covered at night so enemy submarines and warships couldn’t locate targets. Cutler remembered, her father, William – who owned Zall and Sons distribution company in Plymouth – serving as an air raid warden.

“He would ring a bell and tell people to turn off their lights,” she said. “I got to go out with him at night a few times and I felt so grownup!”

The fighting ended before the Class of 1946 graduated, but that didn’t prevent Shaw from becoming a World War II veteran. He joined the 82nd Airborne Division the day after he received his diploma and served with the U.S. Army’s occupation force in Germany.

“I made 20 (parachute) jumps,” Shaw said with pride. When asked how his body has held up after the rigors of football and military service, he noted, “I’ve had both knees replaced and one of my hips, too. I’m due to have the other hip replaced.”

This year, the friends met at East Bay Grille overlooking the Plymouth waterfront for their annual reunion. In an out-of-the-way corner of the restaurant, they quietly reminisced about the good old days. Much has changed in the past 78 years, but life goes on. When asked about a favorite memory, they all agreed that simple pleasures were the best.

“Getting a five-cent ice cream cone,” Monti said. “That was the end of a beautiful day.”

Dave Kindy, a self-described history geek, is a longtime Plymouth resident who writes for the Washington Post, Boston Globe, National Geographic, Smithsonian and other publications. He can be reached at davidkindy1832@gmail.com.