Noah Petitt has been house hunting in Plymouth for two years now. He scours Zillow listings faithfully and tours any property that looks like even a remote possibility. But the homes often turned out to be teardowns, or they’ve drawn so many potential buyers that he didn’t stand a chance.

He feels thwarted at every turn — even with a seemingly healthy budget of $700,000.

Instead Petitt — who works for his family’s business, Plymouth Charter and Cruises — is stuck in an 800-square-foot, one-bedroom rental in North Plymouth.

Once upon a time – actually, just five years ago — potential buyers had their choice of reasonably priced single-family homes in Plymouth, where prices long trailed those in communities closer to Boston. They remain lower today, but “lower” is relative in a hot market driven by low inventory and unrelenting demand.

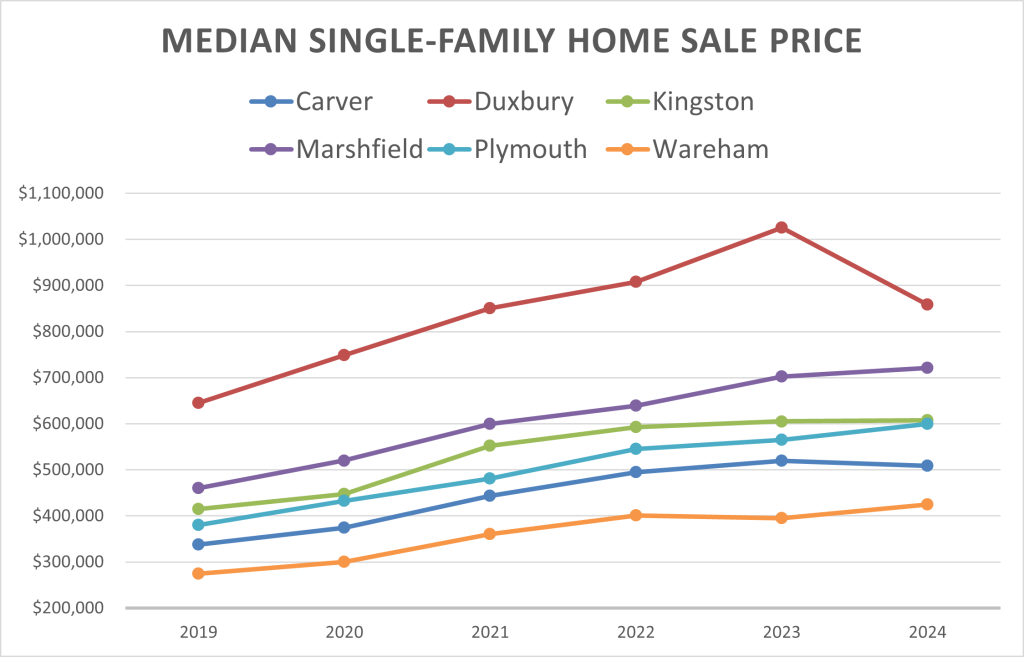

In 2019, the median sale price of a single-family home in town was $379,999, according to data provided by the Warren Group and the Plymouth County Registry of Deeds.

This year, in the quarter that ended in March, that number jumped to $600,000 — an increase of nearly 58 percent in less than five years. (The median price means half of the homes sold above that figure and half sold below it.)

Most houses currently on the market are priced even higher than $600,000. On May 23, the median price of a single-family home for sale in Plymouth was $799,000, according to Multiple Listing Services data provided by Leon Lopes, vice president of COMPASS South Shore and a veteran Plymouth real estate agent.

Throw in a few additional factors like high interest rates and a growing population — and finding your Plymouth dream home at a good price seems nearly impossible.

“If you look at homes by price range, it wasn’t that many years ago that the heaviest numbers in Plymouth were in the $300,000s and $400,000s,” said Lopes. “Now they’re in the $500s and $600s.”

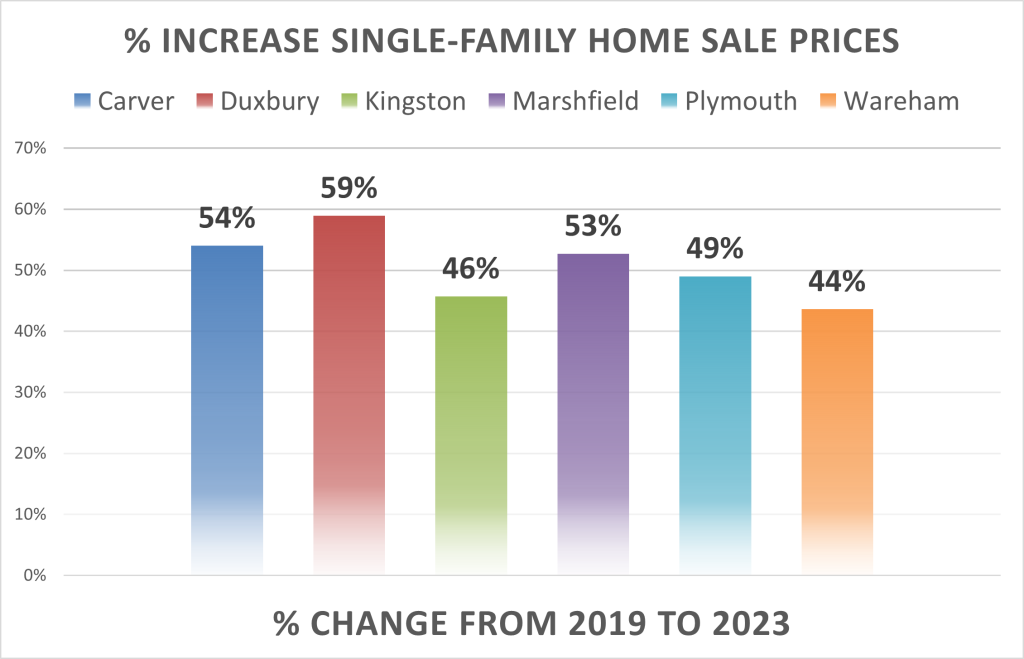

The numbers aren’t much better in neighboring towns.

In Carver, for example, the median price of a single-family home jumped from $337,700 in 2019 to $509,000 in early 2024, an increase of more than 50 percent.

Ditto in Kingston, where the median home price in 2019 was $415,000, but by 2024 reached $607,500. In Wareham – considered one of the region’s most affordable towns -the 2019 median price was $275,000, but has increased to $425,000, according to the Warren Group.

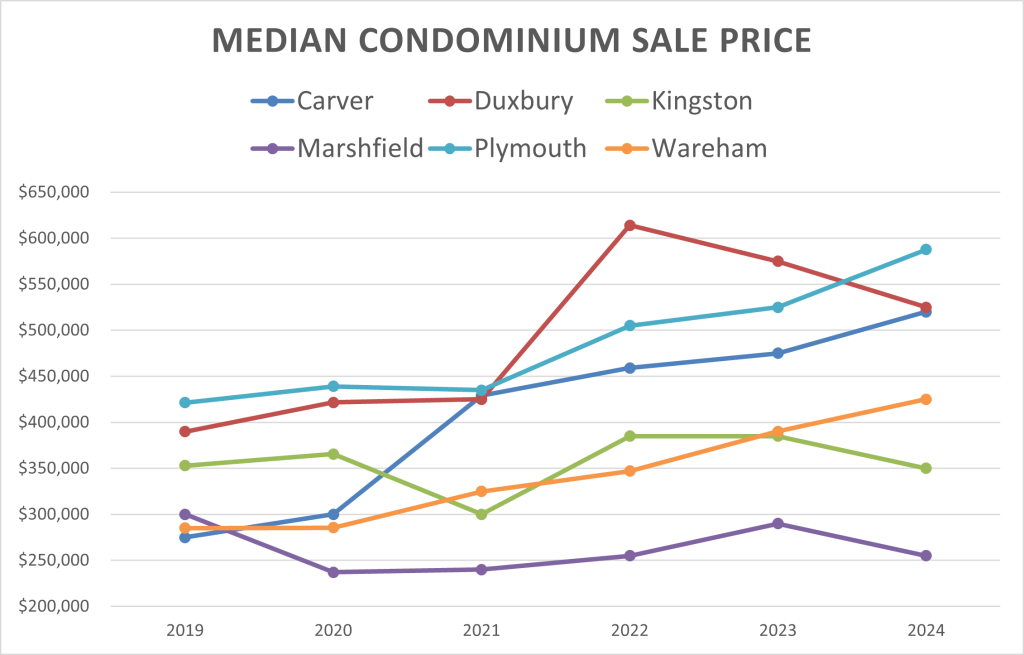

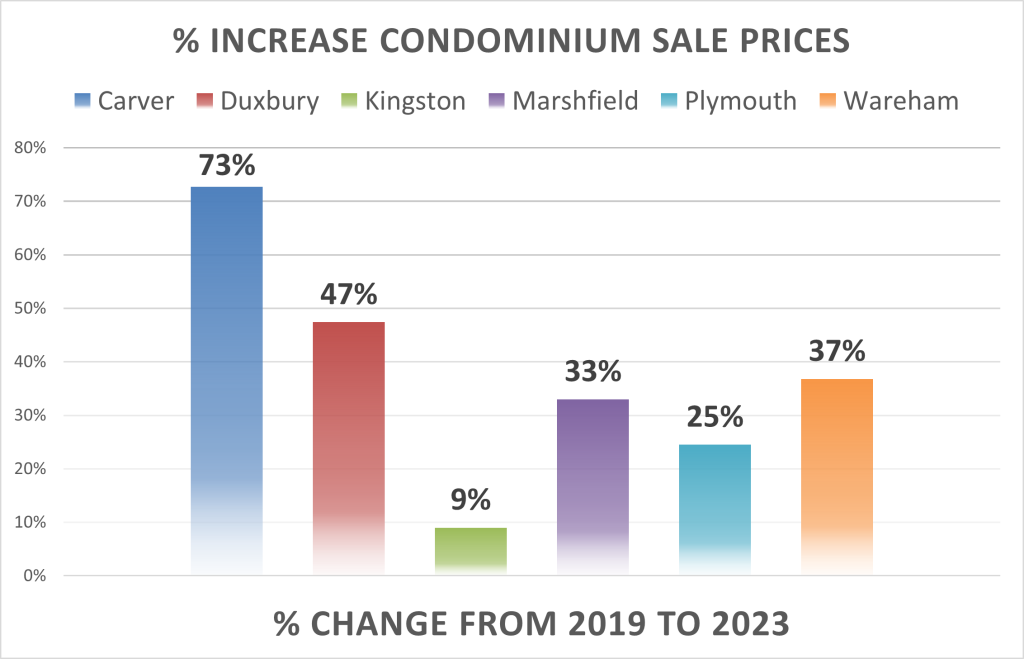

Condominium prices have also increased, though nowhere near as dramatically as single-family home prices. In Plymouth the median price of a condo in 2019 was $421,482. As of the end of March, that number was $587,638 (a 39 percent increase).

And inventory, though slightly better than it has been, is still low. That’s partially because homeowners who might want to sell can’t afford to. Many locked in a low mortgage rate during the pandemic when the Federal Reserve dropped its benchmark lending rate to near zero to stave off a recession. While that rate mostly affects borrowing between banks and doesn’t directly dictate mortgage rates, it sets the tone.

Today, the interest rate for a 30-year fixed rate mortgage hovers at around 7 percent. That’s still not bad historically, but compared with the recent stretch of dirt-cheap borrowing, it’s a deterrent to many potential buyers and sellers.

“Why would you sell your house with a 3 percent interest rate to swap it into a 7.5 percent interest rate,” said Mark Anderson, Redfin principal agent who sells homes in the Plymouth area.

“We have very little supply — it is so restricted that we’re still seeing every month the average sales price keeps going up,” Anderson said.

In 2007 and 2008 – just prior to the housing market’s collapse – there were more than 500 single-family homes on the market in Plymouth, Lopes said. On May 23, there were just 84— and a large number of those are new construction homes built by Toll Brothers in the Pinehills, where the prices are generally more than $1 million.

With so few homes for sale and so many people looking to live in Plymouth, there are no signs of price increases cooling any time soon.

According to the US Census, Plymouth’s population grew 6.8 percent between 2020 and 2023 — the second largest increase in the state. The town now has 65,405 residents, the census figures say, not counting its summer-only population.

Anderson said the only people who are moving are those who have to — because of a family situation or a job relocation.

Others are staying put.

“A lot of buyers have backed off because they can no longer afford to buy — compared to in the past…I have a huge database of people looking to buy,” Anderson said.

He said many of the people still in the market here are in their 30s or 40s and looking to live in the downtown area, where there is little space for new construction and price hikes have been especially dramatic.

“They want to walk to the waterfront or want easy access. They’re not in their 20s — they can’t afford anything here,” Anderson said.

Even if interest rates drop, Anderson said, there will still be a disconnect between potential buyers and sellers because prices will remain higher than many buyers can afford. No one is expecting prices to plummet like they did after the 2008-2009 calamity. The real estate market cratered then largely because it had been flooded with subprime mortgages that failed, triggering a tidal wave of foreclosures. Today’s economy, even with lingering inflation, is on solid ground. That’s good for homeowners building equity but disheartening for anyone looking to get into the market.

“There are a massive number of millennials in their parents’ basement or renting a tiny apartment for $3,500. I don’t know how people can afford to live in Massachusetts. The property taxes, the real estate prices — it’s insane,” Anderson said.

Houses that were once priced moderately now go for close to a $1 million, he said, citing a listing in the Ponds of Plymouth subdivision with an asking price of $965,000.

Cassidy Norton, associate publisher of the Warren Group which publishes the real estate and financial industry bible Banker & Tradesman, said Plymouth’s market trend appears consistent with the rest of Eastern Massachusetts.

“There are only a few things that really force the housing market to dramatically reduce prices,” she said, primarily “an increase in production — more new houses coming into the market which we’re unlikely to see in Massachusetts. “

There’s also a limited supply of land, she said, and it’s expensive. And building costs — including the price of materials and labor — have gone up. Ask anyone who’s undertaken a home improvement project lately.

“It’s an endless loop,” Norton said. “Not enough housing, prices go up.”

As for Petitt, the 24-year-old Navy veteran’s search is made even more difficult because he is financing his purchase with a VA loan. Such loans, available to active and retired military, offer rates that are lower than conventional mortgages and require no money down.

But the government requires inspections for VA loans, and sellers tend to prefer buyers who waive them. Many buyers are offering cash, too, another draw for sellers.

Petitt tried to entice a homeowner by offering $40,000 more than another buyer on a house he really wanted. But his offer was rejected — the sellers didn’t want to wait for an inspection.

“We’ve gone to the distance of writing letters to the sellers,” he said in an interview, “begging them to accept our offer. Still nothing.

“So, I’m overpaying for my 1-bedroom, 1-bath apartment, 800 square feet,” he said.

His rent: $2,600 a month, plus utilities.

Andrea Estes can be reached at andrea@plymouthindependent.org.