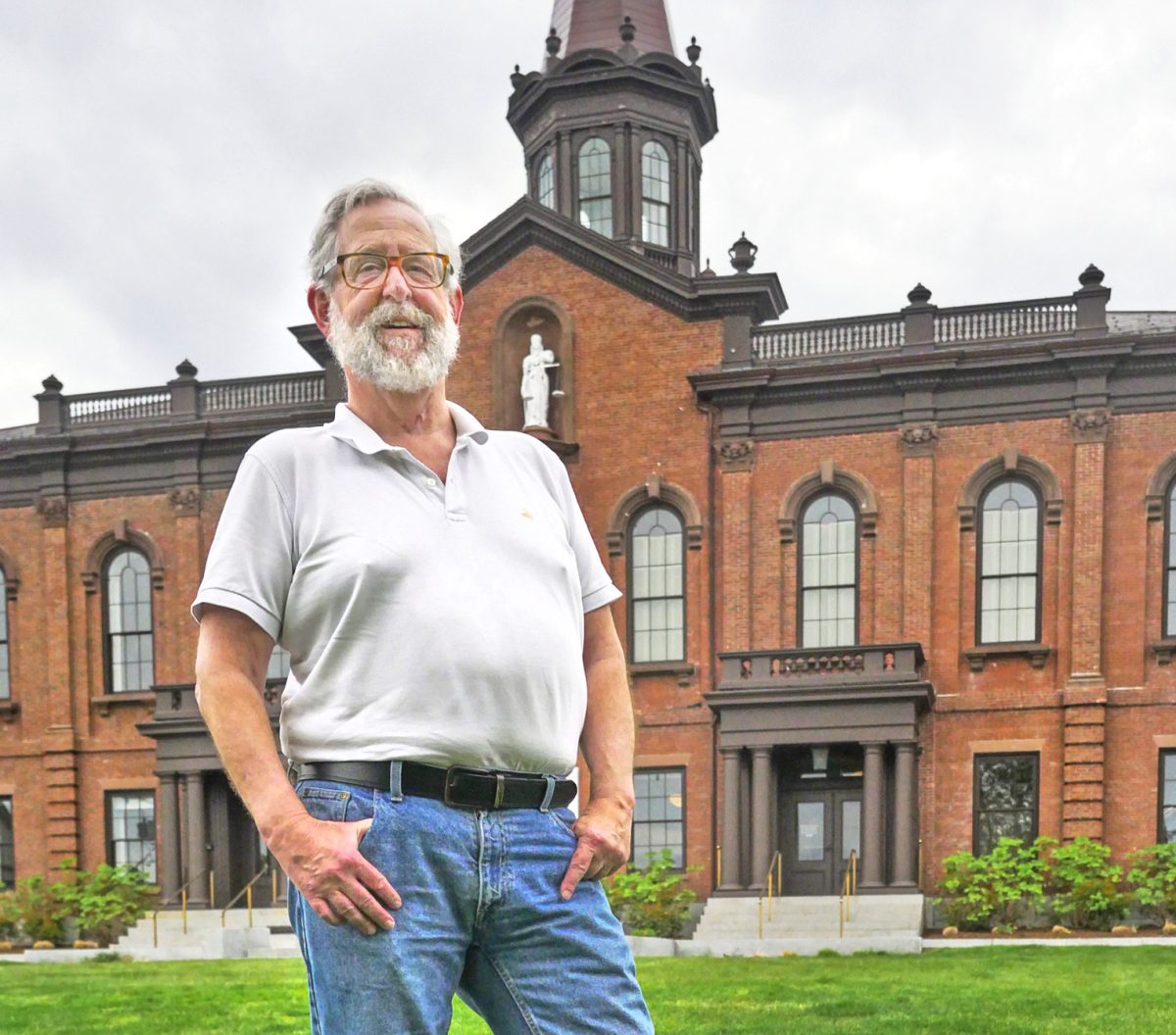

Harry Helm’s long connection to the Plymouth area is about to become a long-distance relationship.

After 30 years of living in town and 11 serving in local government, Helm is moving to Maryland with his husband, Tom.

But leaving isn’t easy. Had he decided to stay in Plymouth, Helm says, he would have run for a seat on the Planning Board in Saturday’s town election.

The town has felt like home to the Helm family for a long time. Helm’s ancestors, some of whom came over on “the boat,” as he calls the Mayflower, bought a piece of Kingston in the late 1700s. By the time he was growing up in Pittsburgh, the family still had the original house in Kingston, built in the 1600s.

Years later, in his thirties, Helm was working in publishing in New York and living in Connecticut when he stumbled onto Plymouth. Unable to afford to buy a house in New York or its Connecticut suburbs, he decided to buy what he calls his “retirement house” in a place he could afford. He spent Saturdays exploring towns on Cape Cod. Then one day, stuck in traffic on Route 3 in Cedarville, he got off the highway and checked out Manomet Point.

A house was for sale.

Thirty years later, Helm is moving from that house in Plymouth for a home in Maryland. He and his husband have found a place there where Helm can devote himself to a lifelong ambition – to write. It also has a garage he can convert into a studio for making stained glass, another of his passions.

For the first 20 of his 30 years in Plymouth, Helm did not get involved in town government. He was commuting to Connecticut, where he shared a home with his late partner, on Sundays, returning on Thursdays. Then 12 years ago, he decided to live at the beach in Manomet full time.

He volunteered for an appointment on the Advisory and Finance Committee, on which he served for eight years, and then ran for the Select Board in 2021, winning election on his first attempt.

In a wide-ranging interview with the Independent, he said he is deeply concerned about rising residential property taxes and their impact on the ability of older residents to age in place.

“A lot of those [people] have been residents here their whole lives,” Helm said. “Their families have been here for generations.”

He said he is most proud of the work he has done to get Plymouth designated as an age- and dementia-friendly community by the World Health Organization and the federal and state governments.

“Age- and dementia-friendly designation opens up the ability for grant funding to help things like transportation,” he said. “We have terrible public transportation, almost non-existent, in Plymouth.”

He said the idea of being able to age in place resonates with him. When he was growing up in Pittsburgh, his father, who ran a restaurant, was offered a job to work for a major frozen foods company but turned the offer down to keep his children close to their grandparents.

To alleviate the pressure to raise residential property taxes, Helm said much of the town’s commercial retail property should be rezoned for light industry and offices.

“More big-box stores, you’re not going to get them, because the whole retail industry is totally on its head right now,” he said.

Helm said his most difficult moment on the Select Board was probably this year’s vote to increase overall property tax revenue by 6.9 percent at a time when values have been rising sharply, along with the price of essentials like food and utilities.

Helm was the lone dissenter on the five-member board. He voted no partly because the increase was too dramatic, he said, but also because he objected to how the budget process played out. The School Committee approved a $199 million budget, and the Select Board went along with it. But School Superintendent Christopher Campbell told board members he would return to ask for more money later in the year, after a contract with the teachers union is negotiated. Since that meeting, Campbell has said $2 million in budget cuts will be needed.

To Helm, the way the budget was handled does not represent strong leadership.

“Good government should not have been ‘this is what we’re asking for, and by the way, we’re going to ask for some unknown millions more at the October Town Meeting,’” he said.

With his term over as of Tuesday evening, and he prepares to leave Plymouth, Helm also worries about what he calls an existential threat – overdevelopment.

“Overdevelopment will kill this town,” he said, referring to the building of more apartments and houses. “Because that will drive taxes through the roof.”

He points to the need for additional fire stations to accommodate the growing population, which is now about 70,000.

Another other dire threat, Helm said, is the degradation of the town’s sole source aquifer as building continues unabated.

“We are on top of our water supply,” he said.

To control development, he has been working with a small group of people, including his colleague on the Select Board, Kevin Canty, newly elected Select Board member David Golden, and Steve Bolotin, vice chair of the Planning Board, to create a land bank, like the one Cape Cod had and Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket have.

The land bank as envisioned by Helm and his collaborators would be funded through real estate transactions by charging buyers a two percent land transfer fee. Someone buying a $600,000 home, the median price in Plymouth, would pay a $12,000 fee. First-time homebuyers and Plymouth residents selling a home to buy another would be exempt from the fee.

Like Community Preservation funds, land bank money could be used to preserve open space and to buy land for affordable housing, but it could also be used to set aside land for schools, fire houses, and police stations, which cannot be funded through the Community Preservation Act.

“The only way to protect the land is to own it,” Helm said. “How can you control your own developmental future when you have a state that is willing to totally override you and incentivize developers to ignore you?”

Helm was referring to the state’s 40b law, which allows developers to avoid some zoning restrictions if less than 10 percent of a municipality’s housing is categorized as “affordable.” That definition is built around incomes based on household sizes.

He hopes the land bank will be proposed at fall Town Meeting as a home rule petition. A yes vote would authorize Plymouth to ask the state Legislature to allow it to create a land bank. If the Legislature approves, a town election would decide whether to move forward.

If a land bank were in place, Helm said, the town would have been able to buy Camp Bournedale, a private summer camp in South Plymouth that’s for sale for $12 million. Now, however, there’s a strong chance that whoever buys it will develop the land.

He said he was inspired to support a land bank in part by a conversation he had with Bill Keohan, chair of the Community Preservation Committee. Helm said he asked Keohan how much of the approximately $4 million a year Plymouth collects in Community Preservation funds he was willing to commit to open land.

The Community Preservation Act requires municipalities to commit at least 10 percent of the funds annually to open land acquisition, with at least another 10 percent going to historical preservation and affordable housing each. It also allows up to five percent to go to administrative costs, with the remaining 65 percent to be spent at the Community Preservation Committee’s discretion.

Helm said Keohan refused to commit to a specific amount of money going to open land acquisition every year.

“He’s the chair of the CPC and he can do what he wants,” Helm said. “He doesn’t have to do what Harry Helm wants.”

But Keohan said he doesn’t have the sole authority to make such promises.

“No one committee member can promise a selectman a certain amount of money to be spent here or there,” he said. “The committee makes the decision. I could not guarantee to the Select Board that we would spend a certain amount of money on open space.”

Helm and Keohan have had their differences, most recently when Helm asked for a Select Board hearing to potentially remove Keohan from his role on the Community Preservation Committee, after misstatements he made at Town Meeting in April about a planned affordable housing development on Court Street. Helm’s remarks prompted a surge of support for Keohan in letters to the Independent and elsewhere, and prompted an unsuccessful last-minute write-in campaign to elect him to the Select Board. (The seat was won by Golden, the only candidate on the ballot.)

Board chair Dick Quintal has since said there will be no hearing to consider removing Keohan, whose current term is up at the end of June.

After castigating Keohan during a recent Select Board meeting – at which Keohan was not in attendance – Helm is now in a conciliatory mood.

“It’s water under the bridge at this point, or to mix metaphors, it’s in my rearview mirror,” he said. “Bill has done amazing things for this town, and the amount of time and commitment that he has given to this town is unassailable.”

One of the hardest things the Select Board must overcome, he said, is misinformation. He cites the recent debate over allowing cruise ships to dock at the town pier (the town agreed to it). Concerns were raised about the ability of lobstermen and fishermen to have continued access to the dock.

Helms said cruise ships won’t have a detrimental effect the local fishing industry.

“They have a whole area. We’re going to have a cruise liner. It’s not going to take the entire dock,” he said. “It has not, so far, after two trips, interfered with the lobstermen’s ability to get traps out or to get traps back in. And yet it became this concept of the town doesn’t care about our fishermen.”

Helm also is troubled by a problem endemic to local government – residents’ lack of participation. He cited races for Town Meeting representative in Saturday’s town election as an example. (This interview took place prior to the election, which generated an anemic 13 percent turnout.) Several precincts had fewer than three candidates for three Town Meeting Member positions. Just as bothersome was the fact that Golden was the only candidate on the ballot for Select Board in a town of about 70,000 people.

“I have no idea” why, Helm said. “Our form of government depends on residents [on] committees. This is a participatory form of government.”

Reflecting on Saturday’s meager voter turnout, he added in a text message Monday that residents do not believe town government is working.

“They see increasing taxes but perceive less services,” he said. “They look at our roads, our facility and infrastructure maintenance, the performance of our students and ranking of our schools. And they perceive failure.”

“They see the overdevelopment of our town and don’t understand why the government can’t stop it,” he continued, saying residents have “decided it’s a waste of time to bother voting.”

Fred Thys can be reached at fred@plymouthindependent.org