In 2018, I made my first trip to my ancestral homeland of Bologna, Italy. Part of the trip included excursions into the countryside to see the villages different branches of my family came from. The village of Palata Pepoli was home to two branches of my family – Fornaciari and Fiocchi. It was everything you could imagine a rural Italian village to be. The downtown core was as quaint as the village setting of North Carver. A small stucco church painted in Tuscan red and marigold yellow anchored a tree-lined street in the village center. Small stucco homes with red-tiled roofs surrounded the church, with acres upon acres of farmland stretching out as far as you could see.

The Fiocchi farm is still in existence just southeast of the village center. The house itself is in partial ruins and the property is now owned by a large agricultural conglomerate. Heading northeast out of the village center is the Pepoli Castello, the summer estate of the powerful Pepoli family from Bologna. (The Fornaciari farm has yet to be pinpointed, but it is thought to be generally southwest of the village center.)

The entire scene was idyllic. Of course, I had dreams of buying a rustic Italian farmhouse in the place of my family’s origins (even though the cost of real estate in that part of Italy rivals what we see in Plymouth). We made the excursion with our close friend and tour guide, Fabio Bergonzini (who has distant relatives in Plymouth). I asked Fabio why anyone would want to leave such a beautiful place. As a city boy from Bologna, Fabio couldn’t imagine living in a rural area. We had a serious conversation about migration to America, and particularly Plymouth.

The Bolognese countryside in the late 1800s was very different than it is today. The Po River was uncontrolled, and the river valley was rife with malaria. In addition, most of the land was controlled by wealthy landlords. In my family’s case, the land was most likely owned by the Pepoli family, and there was a good chance they were tenant farmers. Life certainly wasn’t idyllic.

Flashing back to 1824 sets the stage for the connection between Plymouth and Bologna, and my family’s decision to emigrate from Italy.

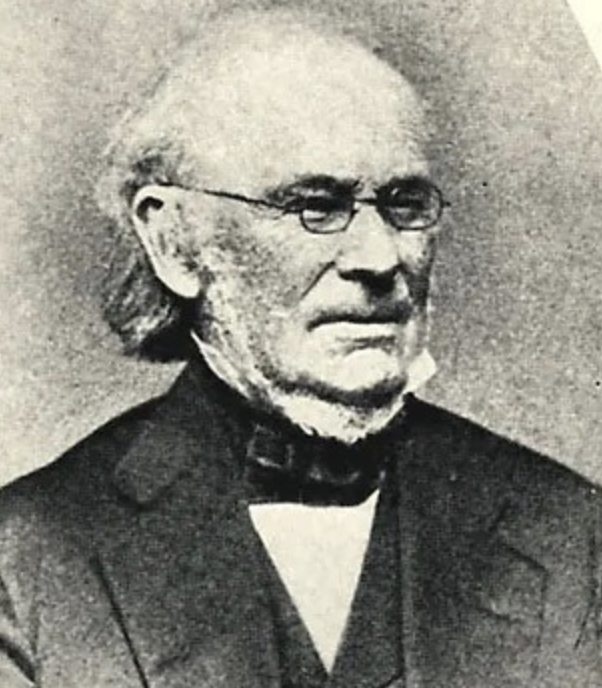

On June 12, 1824, Bourne Spooner – along with investors William Loring, John Dodd, and John Russell – incorporated the Plymouth Cordage Company. “Cordage” was the term used for rigging ropes needed on ships of the era. Although rope production existed in Plymouth prior to 1824, it wasn’t produced in the size and diameter needed for rigging vessels of the 1800s.

Spooner had been fascinated with rope production and traveled to Louisiana in 1812 to learn more about the process. What he saw there shocked him. Labor was provided by slaves suffering through deplorable living and working conditions. The entire process was also grossly inefficient. Spooner realized that giving workers a decent wage, a safe working environment, and a place to live would produce a better product, happy employees, and a sustainable business.

In quick succession after incorporation, Spooner secured 45 acres in Plain Dealing – the then name of North Plymouth. The parcel included 130 feet of ocean frontage and a brook. Ocean access was required for shipping (rail service didn’t arrive in Plymouth until 1845), and running water was required for generating power.

In March 1825, construction began on three structures. They included Spooner’s residence and a six-family residential building, which featured a living room, kitchen, pantry, two bedrooms and two fireplaces. Rent was set at $40 a year (or $1,200 in 2024 dollars).

The ropewalk was the last structure to go up. For those unfamiliar with the process of ropemaking, it begins with the carding, or raking, of the fibers out of a plant. It’s very similar to the process of shredding meat for a pulled pork sandwich. In the first few years of rope making, the hemp plant was used for its fibers. Later, fibers would be extracted from the agave plant and known as sisal. In the last years of production, manila fibers would be extracted from the banana plant.

Shipped to Plymouth from Boston, the hemp arrived on ox carts. The fibers, once raked into long, thin strands, were then twisted together to form strands. The strands would be twisted together to form a piece of rope. To produce strands that were long enough, workers would walk and twist them together in a long building, hence the name “ropewalk.” The first ropewalk structure was more than 1,000 feet long. Eventually, it would be extended to 1,600 feet and almost reached the Kingston line.

Spooner’s endeavor was wildly successful. After construction was completed on the ropewalk in March 1825, the first order for rope was placed by Kingston shipbuilder Captain Joseph Holmes in May 1825. Spooner’s initial workforce of 35 would continue to grow, as did the need for skilled workers. A turning point for the company came in 1870. Bourne Spooner died that year, and the company began looking to Europe to find those skilled workers. One place in particular that was familiar with cordage production was Northern Italy, and the areas around the city of Bologna, which were also home to fields of hemp.

The first wave of Italian immigrants who came to work at Plymouth Cordage Company began in the 1870s. They were also joined by smaller numbers of German and Portuguese immigrants. Word spread throughout the greater Bologna area about a company in America providing employment and housing. The first Italian cordage workers soon encouraged family and friends to join them.

In 1880, my twice widowed 55-year-old great-great grandfather Giovanni and his unmarried 21-year-old son – my great grandfather Primo – left Bologna by train and headed to France. In Le Havre, France they boarded a steamer ship to Boston.

It’s unclear whether Giovanni went to work at Cordage, but Primo did. Shortly after arriving in Boston, Primo married Carolina Fortini and headed south to Plymouth and a job at the Plymouth Cordage factory. Primo was eventually joined by brothers, cousins, aunts, uncles, and neighbors who had all come from Italy.

At its peak in 1910, 2000 people were employed at Plymouth Cordage. They included numerous workers from my family. It’s an integral part of my history and the town’s.

The accolades the Plymouth Cordage Company compiled throughout history reads as an impressive resume. Among them were the title of the world’s largest rope producer and supplier to the USS Constitution. It provided for employees like no other company. Besides housing, the company offered social, health, and education services. It built oceanside bathing pavilions and libraries, too. It sponsored sports teams and company outings. The list could fill a book. Production ceased in 1964 due to the introduction of synthetic rope to world markets. The company had tried to diversify but the handwriting was on the wall – competition from modern materials proved fatal.

The site today is a far cry from its heyday. Some of the mill buildings have been repurposed into offices, medical facilities, and startups. Some buildings have been destroyed. Spooner’s home is now a funeral home, and the first multi-family residence is now a condominium complex. Large residential buildings dominate the site. A bright spot in this complex is the Cordage Museum. It’s located in the red brick mill building in the center of the property and is open Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, and Saturday from noon to 4 p.m. There is a good chance Lucile Leary or David Malaguti (both related to me) will be there. Their knowledge of Cordage is vast. I often find myself visiting after a doctor’s appointment and can easily lose an hour without realizing it.

So, thank you, Bourne Spooner. Your ideas set in motion a series of events that charted my future 200 years ago as of June 12.

Architect Bill Fornaciari, a nearly lifelong resident of Plymouth, is the owner of BF Architects in Plymouth. His firm specializes in residential work and historic preservation. Have a question or idea for this column? Email Bill at billfornaciari@gmail.com.