The inmate, who was being held at the Plymouth County Correctional Facility on an armed robbery charge, liked to talk.

On a single day in April, he sat on the phone for seven hours and 13 minutes, according to the sheriff’s department. When the calls automatically disconnected at 30 minutes, the inmate just redialed, officials said.

He may not have been able to chat for so long were it not for a new law that took effect in December — it allows prisoners in state and county correctional facilities to make unlimited free phone calls to anywhere in the world.

At the time, the law made Massachusetts the fifth state in the country to allow state prisoners to make free calls. It was the first state to allow free calls from county jails, supporters said. (Jails typically hold people charged with lesser offenses than those incarcerated in prisons.)

Advocates say the law strengthens the bonds between inmates and their families and will make their transition to freedom easier.

But crime victims, especially domestic violence victims, say it makes it easy for their abusers to torment them.

Like it or hate it, the law has had a huge impact — prisoners are spending way more time on the phone — and the state and sheriffs are paying for it.

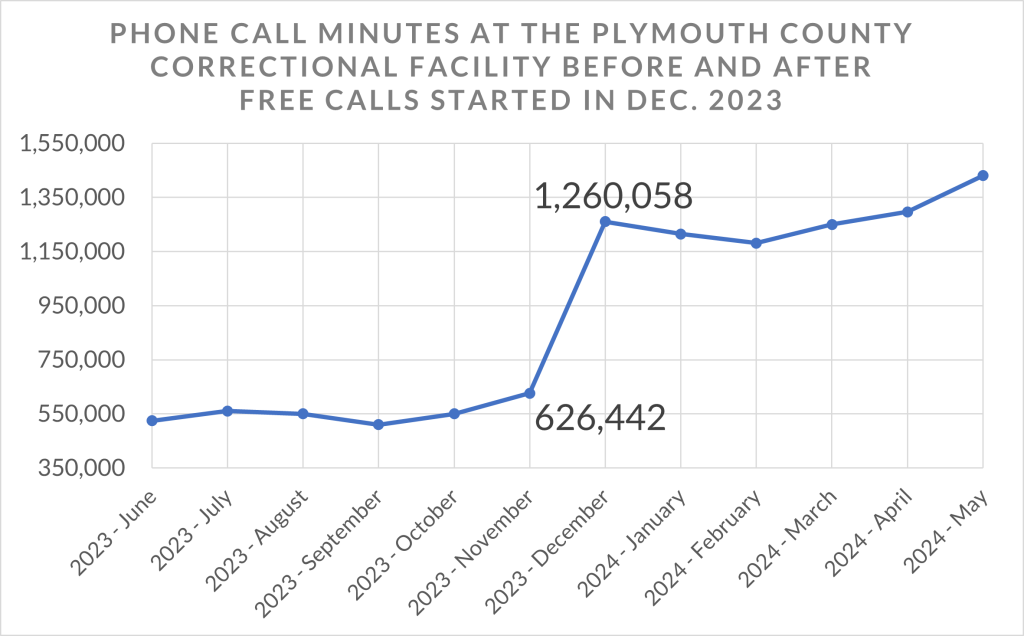

According to data provided by the Massachusetts Sheriffs Association, the state Department of Correction and Plymouth County Sheriff Joseph McDonald, prisoners are spending twice, and in some cases three times, as much time on the phone than they did before the law took effect.

They can make free calls— and in some facilities text or video chat — for as long as they want, generally between early morning and 9:30 or 10 p.m. They can use jail phones, or their state authorized tablets. The calls are cut off automatically after a period of time, but inmates are free to just redial and resume the conversation.

All calls at county jails and state prisons are recorded and subject to monitoring.

One day in April 2024, inmates at the Plymouth County Correctional Facility spent more than five times as much time on calls than the same day in April 2023 — 43,062 minutes compared with 8,181.

Across the state, inmates in the state’s 13 county jails spent more than 13 million minutes on the phone in April, more than twice the number in November 2023 (6.3 million), the month before the law took effect, according to the Massachusetts Sheriffs Association.

Before calls became free, inmates and their families were paying a lot to make calls – up to 14 cents a minute, and 12 cents for state prisoners. The sheriffs were collecting commissions from the vendor that runs the jail and prison phone systems, Securus Technologies. Prisoner rights advocates say inmates were being gouged.

County sheriffs and the Department of Correction are now paying much less per call— 5.9 cents a minute. But the overall cost is still enormous.

The total bill statewide for April 2024 was more than $1.6 million (about $77,000 in Plymouth County alone). Over a year, it would approach $20 million.

That is the amount that Legislature set aside to reimburse the state prison system and the county sheriffs for this year’s calls.

But it’s unclear whether reimbursements will continue in the future. In next year’s proposed budget, the House set aside $35 million to cover the cost, but the Senate version includes no funding. A final budget hasn’t been approved.

Whether unlimited free calls are good or bad depends on whom you ask.

“Access to free communication is a crucial step in fostering a more compassionate and transformative justice system,” said Jesse White, policy director of Prisoners’ Legal Services of Massachusetts, a group that provides lawyers for incarcerated people.

“We look forward to working with the prisons and jails to ensure that they are able to maximize access as the legislation requires.”

Khalil Survey, an immigration detainee who has been in the Plymouth jail for 14 months, said the law hasn’t made a major difference in his life, but has helped a lot of other inmates.

“It’s good for a lot of people who get to talk to their families — especially if they are making international calls. They have long conversations. But I don’t know how long it’s going to last,” said Survey, who is facing deportation after being convicted on child pornography charges.

He also complained that unlike other facilities, Plymouth doesn’t offer text messaging or video calls.

A spokesman for the state’s Executive Office of Public Safety and Security, which oversees the Department of Correction, said the new policy “has removed barriers for incarcerated individuals to stay connected to their outside support network and will promote community safety by improving outcomes for incarcerated individuals upon release.”

But victims and their advocates, as well as Sheriff McDonald, said the law, though well intentioned, has had the unintended consequence of giving abusers unfettered access to their victims.

They say the unlimited free calls puts victims in almost constant fear — even if a prisoner’s number is blocked. They say offenders know how to work around the system.

“Abusers are very clever and manipulative,” said Sandra Blatchford, director of the Plymouth-based South Shore Resource and Advocacy Center.

The policy, in theory, could enable offenders to rebuild relationships with their children or partner. But that would require the abusers to believe they did something wrong, she said.

Many are in denial, she said, and they call incessantly to let the victims know “I’m here and you’re going to answer to me.”

“It becomes very intrusive and scary,” Blatchford said. “They take this as an opportunity to call the victim all day long.”

State representative Alyson Sullivan, (R-Abington), an abuse survivor herself, was one of only 26 House members to vote against the measure.

She endured years of physical and emotional abuse by a former boyfriend, who was arrested and held in the Plymouth County Correctional Facility.

“The phone calls are nonstop,” she said.

“Can a victim block the phone number? Yes. But speaking as someone who has survived years of trauma, it’s not as easy as it seems. When my abuser was in jail, I’d get calls from people I didn’t know…They make phone calls continuously and keep control over their victims,” Sullivan said.

McDonald said not only does the law give abusers a way to keep victimizing people, but it also lets some defendants “operate their outside criminal enterprises at the public’s expense.”

“While I am supportive of the goal of family contact and ultimate reunification, this misguided legislation must be amended to include reasonable controls and time limitations on free calls,” he said.

Andre Estes can be reached at andrea@plymouthindependent.org.