This is the second installment of a two-part series on recycling in Plymouth. You can read the first installment here.

Recycling is like the world – complex and imperfect. But Plymouth residents can make it work better.

First, if you are not yet recycling, start. Second, if you are recycling, learn to correctly separate trash from recyclables. Most of us make mistakes that can slow – and even clog – recycling facilities’ operations.

The more we successfully recycle, the less that our haulers must take to landfills, which are shrinking in number, and to waste-to-energy (WTE) plants – such as West Wareham’s SEMASS facility – which burns trash to generate electricity.

“Landfills are not a sustainable solution, because we are running out of space; we can’t just keep expanding them forever,” said Ken Stone, of Sustainable Plymouth’s Solid Waste and Plastic Reduction Group. “Waste-To-Energy plants are necessary, but not a long-term solution either, since they create a harmful residue that must be disposed of in landfills and they expel contaminants into the environment from their stacks, especially the older facilities.”

Pinehills resident Michael Hanlon, a retired civil engineer, agrees. “WTEs generate huge quantities of CO2, a greenhouse gas, and are not sustainable over the long term,” Hanlon said.

For over 30 years, Massachusetts has had a moratorium on construction of new waste-to-energy plants. “But we need them for now because they burn up over half of our waste,” Stone said.

Fewer plants locally mean some haulers must travel as far away as Alabama to dispose of their loads, at greater expense, while burning more fuel in the process, explained Claire Galkowski, executive director of the South Shore Recycling Cooperative, which includes 18 communities.

Stone and Hanlon believe the local and national emphasis should be:

1) On reducing how much waste we generate in the first place through deposits on bottles, public education, and passing the Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) bill, which makes manufacturers more responsible for the ecological impact of products they introduce to the market.

2) On increasing access to recycling.

3) On making improvements in waste management and disposal through emerging technologies.

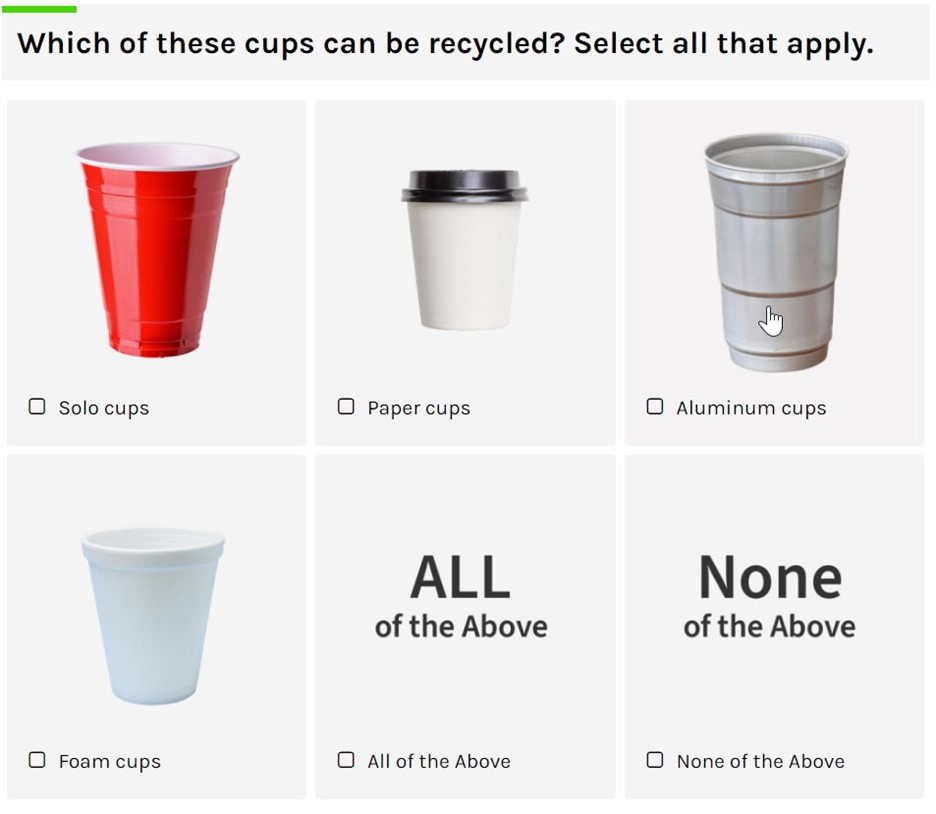

Local environmental groups and town officials point to the RecycleSmart.org website as a good starting point for basic recycling information. This embarrassed reporter took a quiz on the nonprofit’s site and failed to correctly answer many questions. Colored plastic cups? Not recyclable. Paper cups? No. Styrofoam cups? Nope! Greasy cardboard pizza boxes? Yes, recyclable! Scrap metal? No, but scrap metals can be recycled at Plymouth’s Manomet transfer station.

Can you place metal coat hangers in recycle bins? No, bring them back to your dry cleaner. Metal wires? Never. Hangers and wires can gum up the works of the machines at materials recovery facilities.

Plastic forks, spoons, knives? Nope. Too small. Those black take-out containers? No way. Why? Manufacturing Resource Facilities sort plastics with optical sorting systems that use reflected light to determine the type of plastic. Black plastics contain light-absorbing carbon, so optical sorters can’t “see” them.

“These black containers should be trashed or reused,” said a worker at the SEMASS recycling facility in West Wareham.

Should we keep the caps on plastic milk jugs? Yes. According to RecycleSmart.org, lids and caps should be placed back on bottles, jars, jugs, and tubs before recycling.

“Loose caps will literally fall through the cracks at the recycling sorting facility,” Stone said.

Do we recycle cardboard? Yes, but not the Styrofoam or the air-pillow packaging that comes in home-delivered cardboard boxes. Trash that foam. (“Although if you’re traveling to Bridgewater, Insulation Technology accepts clean white foam for recycling,” Galkowski noted.)

What about those much-debated nip containers?

“They are too small to be accepted by recycling machinery,” said Hanlon. (Plymouth residents might already know that, thanks to the recent hoopla over the vote to reverse a ban on nip containers, which was never implemented.)

Plymouth residents also shouldn’t put bubble wrap, plastic packaging used for products such as paper towels, and plastic shopping bags in their recycling bins.

“They cannot be processed at our local transfer stations,” said James Downey, Plymouth’s assistant director of Public Works. “You can bring all these items to your local stores, where they can be accepted for processing.”

Other non-recyclables that must go in the trash: “Loose bottle caps, plastic bread clips, hotel toiletry bottles – anything smaller than 2-by -2 inches will not be accepted,” Downey said.

And add all this to that list of non-recyclables: light bulbs, dishes, kitchenware – like pots, pans, ceramics, and Pyrex – paper towels and napkins, wires, and string lights.

Most recycling blunders are not tragic. They do, however, require recycling facilities to take more time and effort sorting and cleaning their piles of cardboard, aluminum, glass, plastic, etc.

Stone urges people to rinse items containing food before recycling them.

Another issue with recycling is the cost per ton, with each recyclable having its own value. For example, cardboard – which comprises 15 percent of recyclables nationally – recently fetched $105 per ton, the price that the end user pays to the processor for the baled material. Aluminum, which includes aluminum beverage cans, earns the most – $1,100 per ton – “with plastic values right behind it,” she said.

Prices are volatile because recyclables are commodities with no government support, affected by oil prices and other economic factors, according to Galkowski. “Covid had a big impact – positive for some materials, negative for others, notably paper,” she said.

“Paper and glass are low-value materials, while widely vilified plastics have high value and, in fact, maintain the financial viability of recycling.” she emphasized.

What about the impact of the Chinese ban on US recyclables that was announced five years ago? Chaz Miller, a veteran of the National Waste & Recycling Association, wrote that “while the ban has adversely impacted prices, we still have market demand for our recyclables. Paper mills and other manufacturing facilities throughout the world still use local recyclables. After all, it’s usually cheaper to ship locally than overseas.”

Locally, Plymouth residents can dispose of their trash and recyclables by contracting with a local trash hauler approved by the town. (Lombard’s Waste Services – the approved hauler that Plymouth’s Board of Health says has been violating the town’s requirement to separate recyclables from trash – will start a residential recycling program on July 1, according to Lombard’s owner Matt Romboldi.)

Residents can also opt to buy a transfer station permit and pay-as-you go bags, or bring their “discards” to the Manomet transfer station on Beaver Dam Road. Most materials must be separated and dropped at several stations: mixed paper, cardboard, newspaper, glass, and commingled containers.

“Other items like TVs, computer monitors, certain household appliances, propane tanks, antifreeze, motor oil, car batteries, car tires, mercury-containing products, grass clippings and leaves need to be kept completely separate, and may require additional fees per item,” explained Downey.

The transfer station does not accept brush or branches. But the DPW opens its facility off Camelot Drive twice each year for freebrush and branches drop-offs.

Downey said that there’s a separate waste facility adjacent to the Manomet transfer station that charges to dispose of such items that the town facility does not accept. That includes mattresses, construction and demolition debris, bulky items, and carpets. The facility will not take toxic and hazardous waste, automotive fluids, fertilizers, pesticides, or mercury products. Many of those items can be taken to the South Shore Recycling Cooperative on one of its hazardous-waste days. More information about that can be found here.

The JunkLuggers, a commercial recycling hauler that services Plymouth, is one source for residents who need to dispose of contents of a home. “We collect your unwanted items and sort through them, seeking opportunities to repurpose, donate, and recycle,” said Charles “Skip” Dennis, who is The JunkLuggers’ chief lugging officer. (Yes, that’s really his title.) “Our goal is to keep items out of landfills and give them a new purpose whenever possible.”

The JunkLuggers often works with Habitat for Humanity, donating furniture and lighting, and providing the client with a tax receipt. Dennis said it just performed a job for Walmart, recycling tons of spoiled food to be used by compost farms.

Robinson Recycling & Removal in Norwell also provides estimates for picking up and removing both recyclables and trash – from a single item to an entire estate. Recyclables are donated to local charities, said owner Paul Robinson.

HandUp Mattress Recycling, based in New Bedford, provides curbside mattress pickup. Both JunkLuggers and HandUp charge $50 per mattress and per box spring, regardless of bed size. Both firms have sources that recycle mattress components (foam, steel, and cotton).

Beyond typical waste, you can learn where to dispose of everything from acetylene torches to X-ray film by visiting the South Shore Recycling Cooperative’s site.

Unfortunately, some people can’t be bothered to do the right thing when it comes to their household waste, which is why so much trash mars the local landscape, and unwanted furniture ends up slowly decaying on sidewalks or – worse – tossed along roadsides or in the woods.

You can do something to combat that by volunteering to help clean up some of this junk. The town has scheduled volunteer clean up days on May 17 and 18 (rain or shine).

“Join an existing group, create your own, or go solo to clean up a neighborhood, park or roadway that needs attention,” said Patrick Farah, Plymouth Planning and Development’s conservation inspector and energy officer. Register online or at Town Hall, where you can also get purple trash bags that the DPW will pick up at drop-off locations.

Steven Feldman is a real estate agent for Keller Williams Realty, a renovator of Plymouth-area properties, and a former Boston journalist.