The seas were rough that morning 80 years ago. In the early hours of D-Day, June 6, 1944, Sgt. Tom Ruggiero of Plymouth put a paper sack he’d been handed to good use as his Landing Craft Assault (LCA) bounced through heavy waves on the way to Omaha Beach in Normandy, France.

“I had thrown up through my vomit bag,” he later recalled in a video for the American Battlefield Monuments Commission.

As the LCA neared shore, Ruggiero and 21 other soldiers in D Company – better known as “Dog Company” – of the U.S. Army’s 2nd Ranger Battalion were ordered to get ready. Ruggiero moved to the front of the craft to prepare a catapult that would fire a grappling hook to the top of Pointe du Hoc, a 110-foot cliff his unit was assigned to scale so it could knock out German artillery.

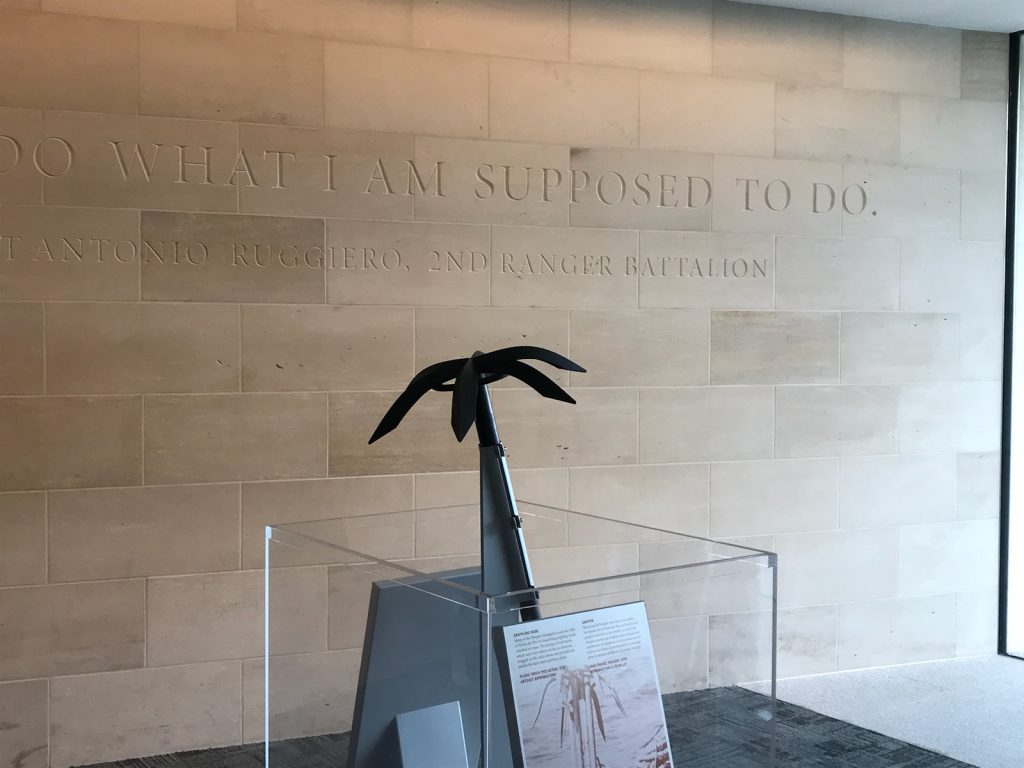

As he worked, Ruggiero looked at the stormy sea and said a prayer: “Dear God, don’t let me drown. I want to get in and do what I’m supposed to do.”

That divine appeal came in handy moments later when a German shell exploded in front of the landing craft, overturning it and sending the men and their equipment flying into the frigid waters of the English Channel. Ruggiero shed his gear and ordered others to do the same.

He said, “I told the men, ‘Keep your legs going like pedaling a bicycle,’” according to Patrick K. O’Donnell in his 2012 book “Dog Company: The Boys of Pointe du Hoc – The Rangers Who Accomplished D-Day’s Toughest Mission and Led the Way across Europe.”

For 40 minutes, the men battled the cold waves while shivering from hypothermia. Ruggiero and several soldiers were rescued by a passing gunboat. Many others were not so lucky, drowning in the pounding surf just a few hundred yards from Omaha Beach. Those who were saved spent the rest of D-Day trying to get warm on an American battleship. They would rejoin Dog Company in a few days and continue the campaign to liberate France. During World War II, Ruggiero – or “Ruggie” as his friends in the Army called him – would see action across Europe, including at the Battle of the Bulge, earning two Bronze Stars for bravery and two Purple Hearts for wounds – one of which nearly killed him.

“He was strong-willed,” Karen Ruggiero recalls about her father, who died at 95 in 2016. “He never gave up. He just kept on going.”

The 80th anniversary of D-Day has many people thinking about the sacrifices made by the Greatest Generation, Karen included. That her dad had put his life on the line to fight for freedom in the world’s deadliest war was something she didn’t fully comprehend until later.

“When I was growing up, he was just my father,” says the former music teacher with the Plymouth school system. “He’d get together with some of his Ranger buddies and then I realized, ‘Oh, OK. Now I get it.’ It really hit me when I went to France and saw Pointe du Hoc. It was very emotional.”

Born in 1920, Antonio Thomas James Ruggiero was known as “Tom” around Plymouth. He was a talented tap dancer and wanted to pursue a career in Hollywood. World War II came along, however, and he decided to serve his country. Ruggie tried to volunteer for the Marines but was turned him down because he was only 5-foot-2-inches tall.

“How tall do you have to be to squeeze a rifle trigger,” he angrily told recruiters, according to a 2014 article in The Patriot Ledger. Undeterred, Ruggie signed up with the Army and talked his way into the Rangers, an elite fighting force styled after British Commandos. Their job was to master dangerous assignments that regular soldiers weren’t trained to do.

On D-Day, Pointe du Hoc was the target for the 2nd Ranger Battalion. The unit had trained to assault the sheer cliff, where Germans were entrenched with artillery that had a commanding view of Omaha Beach. Their mission was to destroy those cannons and save soldiers coming ashore in Normandy.

While Ruggie was battling freezing water, other Rangers climbed up the precarious precipice, enduring machine gun fire and hand grenades as they ascended. Many lost their lives. Once reaching the top, the soldiers learned the artillery had been moved several hundred yards inland. They eventuallylocated the weapons and destroyed them.

Two days later, Ruggie and the survivors from his landing craft finally got to climb Pointe du Hoc. Reoutfitted and ready for action, a captain told them, “You got trained to climb a cliff. We’re gonna climb a cliff.” When they reached the top, Ruggie realized the cord he used was made in his hometown.

“You know, that rope came from the Cordage Company in Plymouth? Three-quarter-inch, believe it or not,” he told The Patriot Ledger.

Ruggie rejoined Dog Company and was thrust into action against the Germans almost immediately. He was on patrol with the unit’s captain when he looked over a hedgerow and spotted a German helmet. He had one grenade but hesitated to use it.

“You have to pull that clutch back on the grenade, and I didn’t want to do it because it makes a helluva noise,” he later said. “They hear it: click-clack. My legs were shaking already, for cripes sake. I wasn’t ashamed to say it.”

He finally tossed the grenade while the captain blasted away with his Thompson submachine gun, killing eight Germans. The captain earned a Silver Star while Ruggie received his first Bronze Star.

The Plymouth soldier earned another Bronze Star for bravery and was wounded twice in combat. He was knocked unconscious in a rocket attack and was cut across his abdomen. Another time, he suffered serious injuries from shrapnel in his face and back. Ruggie had surgery in a military hospital, but the doctors were not able to remove all of the metal. He carried a reminder of that moment with him for the rest of his life.

Ruggie fought across Europe, including at a famous bayonet charge at Hill 400 in the Hürtgen Forest, located along the border of Belgium and Germany. The Rangers captured this strategic position in December 1944 after regular frontline troops couldn’t following weeks of bloody fighting.

“It was something straight out of Hollywood,” he said in O’Donnell’s book. “Someone yelled, ‘Fix bayonets,’ and we screamed and took off.”

After the war, Ruggie returned to Plymouth, started a family and went to work for the fire department, from which he retired as a captain in 1975. Karen says her father rarely talked about his experiences in combat and suffered from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder.

“I slept in the room next to his and my mother’s,” she said. “I remember hearing him screaming in the night. All my mother would say the next morning is, ‘Your father had a bad night.’”

Ruggie finally started speaking about his service in World War II after a soldier friend convinced him it was his responsibility to inform younger generations about what had happened. He went to schools, meetings, and gatherings to tell the story of Dog Company and the men who fought and died for freedom. Ruggie even participated in an oral history project, where he recited the prayer he said to himself on D-Day. Those words are now engraved in stone at the Pointe du Hoc Visitors Center, not far from the cliff scaled by Rangers 80 years ago

“I was so surprised when I visited and saw my father’s words on the wall,” Karen says.

In 1984, Ruggie met President Ronald Reagan in France for the 40th anniversary of Omaha Beach. He also was honored by President Barak Obama in 2009 on the 65th anniversary of the Normandy landings.

During the latter ceremony, he was made a Chevalier of the Legion of Honor for extraordinary courage in liberating France. Presented by French President Nicolas Sarkozy, the medal is the country’s highest civilian honor.

Ruggie died at 95 in 2016, two years after again being in the spotlight at the National Memorial Day Concert in Washington, D.C. In 2014, he was one of several World War II veterans attending the annual program, hosted by actors Gary Sinise and Joe Mantegna.

To the end, Ruggie was proud of what he accomplished as a Ranger with Dog Company, though he never boasted about it. Instead, he always remembered the brave men who were not lucky enough to return home. Karen says she made the mistake of calling her father a hero once.

“I’m not a hero,” he corrected her. “The heroes are buried at Normandy.”

Dave Kindy, a self-described history geek, is a longtime Plymouth resident who writes for the Washington Post, Boston Globe, National Geographic, Smithsonian and other publications. He can be reached at davidkindy1832@gmail.com.