As Plymouth’s Battle of the Nips rages on, here is a brief report from the recent hometown fall cleanup. It’s based solely on personal experience, and therefore not too scientific, but it seems to me like some features of Plymouth’s natural environment just might be improving.

That’s good news for Plymouth Harbor and its tributaries. Several projects in the pipeline—ranging from reversing the discharge of treated effluent to the ongoing restoration of Town Brook— could lead to further improvements. Should the harbor’s eelgrass beds expand as a consequence, they might even contribute to an increase in the natural removal of carbon from the atmosphere, making an important contribution to one of the town’s climate actions.

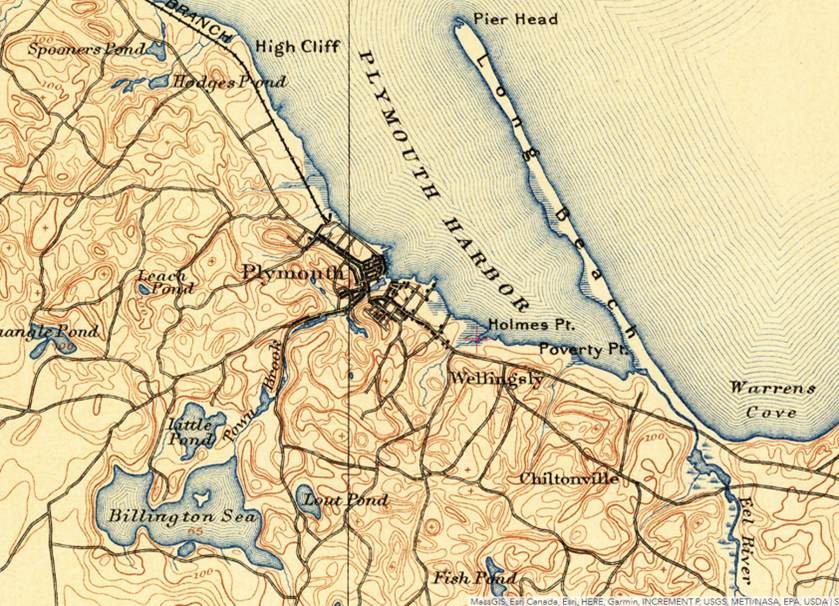

The fall cleanup took place on Saturday, Nov. 4. Usually, my spouse and I do a sweep up Nook Road. On occasion, I also clear litter from the small creek running between Brookside Avenue and Nook Road. The creek, called Hobs Hole Brook, forms a boundary between the communities of historic downtown Plymouth and the settlement of Wellingsly (also formerly referred to as “Little Town”). By my count, it’s one of the six original flowing waterways that empty into the harbor in Plymouth (I’m not including Kingston and Duxbury here).

Here’s a map from 1889:

Walking the thalweg from the harbor at low tide up to the bridge at the unmarked Weston Street, normally I can fill two of the town’s purple cleanup bags with all kinds of discarded items. Typically, I pick up several hubcaps that are the consequence of taking the inside curve too tightly when headed northeast on Nook: screech…pop! We hear it all summer; even Jan & Dean would be startled!

Then there are six-packs of light beer (name your brand), a variety of hard seltzers, plastic iced-coffee cups, glass bottles, potato chip bags, cannabis containers, cigarette packs and butts, shoes, women’s purses, and — always — those ubiquitous nips. They usually comprise the bulk of the semi-annual haul.

It’s important to start downstream from the harbor because of the significant flow in the brook, which suspends sediment from footfalls. That makes it difficult to see submerged litter.

This year the bar at the tip of Holmes Point — when exposed at low tide — exhibited what appeared to be much higher-than-normal numbers of mollusk and crustacean shells. These included mainly softshell and razor clams, quahogs, sea scallops, and a few horseshoe and green crabs. Several live oysters were a surprise. Pretty sure they didn’t just get there on a pleasant walk, but maybe they rolled over from the town leases on the flats north of High Cliff.

Moving upstream, the litter this time was minimal — another surprise. At the rapids deep in what is now predominantly a phragmites marsh, formerly known as Cornish’s Meadow, I disturbed a fish. I couldn’t see it clearly in the dim light. Probably a “salter” or sea-run brook trout, a descendent of the yield of the trout farm that the brook once embodied more than a century ago. But it might have been an eel…

The American eel is one of Plymouth’s most important environmental links to the larger world. In some recent years, as many as 45,000 glass eels and elvers have been counted migrating past the gristmill on Town Brook, using the State Division of Marine Fisheries’ ladder to scale the heights from the brook to Jenney Pond. While a lucrative international market exists for these juvenile eels, their harvest currently is prohibited in Massachusetts.

The American eel’s life cycle begins in the Sargasso Sea, a gyre far out in the Atlantic Ocean. In 1925, the Rhode Island oceanographer Marie Poland Fish identified fertilized American eel eggs in a deep sample taken from the Sargasso Sea near Challenger Bank, just southwest of Bermuda. Upon hatching, eel larvae drift with the Gulf Stream and other ocean and coastal currents, arriving as transparent glass eels and the opaquer elvers at the mouths of estuaries ranging from Greenland to French Guiana. They may be at sea in their larval and glass eel stages for as long as a year.

The eels swim up freshwater streams into quiet stretches and ponds, becoming America’s only freshwater eel species. They reside upstream for two decades or more until they enigmatically “decide” to return to the Sargasso Sea, where they breed and expire. In 2015, the Quebecois biologist Mélanie Béguer-Pon and her colleagues tracked an eel that traveled nearly 1,500 miles from the shelf off Nova Scotia to spawning grounds west of Bermuda. And then the cycle renews.

Even minor streams such as Hobs Hole Brook can serve as eel habitat. I was reminded of this once by my former neighbor Conn Holmes, a lobsterman who rowed to work each day and lived to the very ripe age of 102. Conn told me that his father used to catch eels from the brook for dinner, especially during the autumnal downstream migration. Typically, a moonless, cold, wet November evening is perfect for the start of their journey. They can even crawl overland where a stream may have been blocked. Upon entering the estuary, they begin their herculean swim to spawning grounds in the middle of the Atlantic.

Except for salvaging the occasional oddity (an old brown stoneware jug!) the Hobs Hole Brook was remarkably clean this time. And — if the evidence is real — an abundance of shellfish on the bar off Holmes Point may indicate both a cleaner environment to support their growth and an expansion of their capacity to help keep the harbor clean.

This virtuous cycle might be enhanced further by the realization of proposals to reverse the discharge of treated sewage effluent from the harbor to the sand bed at Camelot and to dredge Jenney Pond and engineer a nature-like bypass around the dam, making it a natural fish ladder for the eels and the alewives, bluebacks, and trout.

And…does it make sense to vote to revoke the ban on nips? No! Yes! Huh? Maybe we should just go back to stoneware jugs…

Plymouth resident Porter Hoagland is interested in local environmental and natural resource matters. He welcomes your feedback, and can be reached at phoagland@whoi.edu.